Wednesday, May 6, 2009

William Egglestone

William Egglestone

American born 1939

William Eggleston was born in Memphis, Tennessee and raised in Sumner, Mississippi. His father was an engineer who had failed as a cotton farmer, and his mother was the daughter of a prominent local judge. As a boy, Eggleston was introverted; he enjoyed playing the piano, drawing, and working with electronics. From an early age, he was also drawn to visual media, and reportedly enjoyed buying postcards and cutting out pictures from magazines. As a child, Eggleston was also interested in audio technology.

At the age of fifteen, Eggleston was sent to the Webb School, a boarding establishment on Bell Buckle, Tennessee. Eggleston later recalled few fond memories of the school, telling a reporter, "It had a kind of Spartan routine to 'build character.' I never knew what that was supposed to mean. It was so callous and dumb. It was the kind of place where it was considered effeminate to like music and painting." Eggleston was unusual among his peers in eschewing the traditional Southern male pursuits of hunting and sports, in favor of artistic pursuits and observation of the world around him.

Eggleston attended Vanderbilt University for a year, Delta State College for a semester, and the University of Mississippi (Ole Miss) for approximately five years, none of this experience resulting in a college degree. However, it was during these university years that his interest in photography took root: a friend at Vanderbilt gave Eggleston a Leica camera. Eggleston studied art at Ole Miss and was introduced to abstract expressionism by a visiting painter from New York named Tom Young.

Artistic development

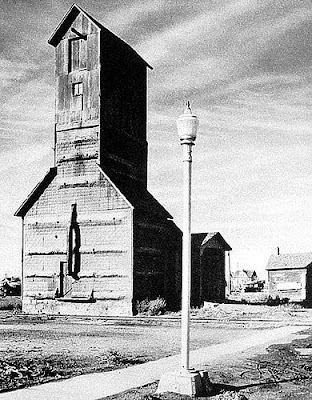

Eggleston's early photographic efforts were inspired by the work of Swiss-born photographer Robert Frank, and by French photographerHenri Cartier-Bresson's book, The Decisive Moment. First photographing in black-and-white, Eggleston began experimenting with color in 1965 and 1966; color transparency film became his dominant medium in the later sixties. Eggleston's development as a photographer seems to have taken place in relative isolation from other artists. In an interview, John Szarkowski of New York's Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) describes his first, 1969 encounter with the young Eggleston as being "absolutely out of the blue." After reviewing Eggleston's work (which he recalled as a suitcase full of "drugstore" color prints) Szarkowski prevailed upon the Photography Committee of MOMA to buy one of Eggleston's photographs.

In 1970, Eggleston's friend William Christenberry introduced him to Walter Hopps, director of Washington, D.C.'s Corcoran Gallery. Hopps later reported being "stunned" by Eggleston's work: "I had never seen anything like it."

Eggleston taught at Harvard in 1973 and 1974, and it was during these years that he discovered dye-transfer printing; he was examining the price list of a photographic lab in Chicago when he read about the process. As Eggleston later recalled: "It advertised 'from the cheapest to the ultimate print.' The ultimate print was a dye-transfer. I went straight up there to look and everything I saw was commercial work like pictures of cigarette packs or perfume bottles but the colour saturation and the quality of the ink was overwhelming. I couldn't wait to see what a plain Eggleston picture would look like with the same process. Every photograph I subsequently printed with the process seemed fantastic and each one seemed better than the previous one." The dye-transfer process resulted in some of Eggleston's most striking and famous work, such as his 1973 photograph entitled The Red Ceiling, of which Eggleston said, "The Red Ceiling is so powerful, that in fact I've never seen it reproduced on the page to my satisfaction. When you look at the dye it is like red blood that's wet on the wall.... A little red is usually enough, but to work with an entire red surface was a challenge."

At Harvard, Eggleston prepared his first portfolio, entitled 14 Pictures (1974), which consisted of fourteen dye-transfer prints. Eggleston's work was featured in an exhibition at MOMA in 1976, which was accompanied by the volume William Eggleston's Guide. The MOMA show is regarded as a watershed moment in the history of photography, by marking "the acceptance of colour photography by the highest validating institution" (in the words of Mark Holborn). Eggleston's was the first one-person exhibition of colour photographs in the history of MOMA.

Around the time of his 1976 MOMA exhibition, Eggleston was introduced to Viva, the Andy Warhol "superstar," with whom he began a long relationship. During this period Eggleston became familiar with Andy Warhol's circle, a connection that may have helped foster Eggleston's idea of the "democratic camera," Mark Holborn suggests. Also in the seventies, Eggleston experimented with video, producing several hours of roughly edited footage Eggleston calls Stranded in Canton. Writer Richard Woodward, who has viewed the footage, likens it to a "demented home movie," mixing tender shots of his children at home with shots of drunken parties, public urination and a man biting off a chicken's head before a cheering crowd in New Orleans. Woodward suggests that the film is reflective of Eggleston's "fearless naturalism—a belief that by looking patiently at what others ignore or look away from, interesting things can be seen."

William Eggleston's Guide was followed by other books and portfolios, including Los Alamos (actually completed in 1974, before the publication of the Guide) the massive Election Eve (1976; a portfolio of photographs taken around Plains, Georgia before that year's presidential election); The Morals of Vision (1978); Flowers (1978); Wedgwood Blue (1979); Seven (1979); Troubled Waters (1980); The Louisiana Project (1980); William Eggleston's Graceland (1984) The Democratic Forest (1989); Faulkner's Mississippi (1990), and Ancient and Modern (1992). Eggleston also worked with filmmakers, photographing the set of John Huston's film Annie (1982) and documenting the making of David Byrne's film True Stories (1986). He is the subject of Michael Almereyda's recent documentary portrait William Eggleston in the Real World (2005).

Eggleston's aesthetic

Eggleston's mature work is characterized by its ordinary subject-matter. As Eudora Welty noted in her introduction to The Democratic Forest, an Eggleston photograph might include "old tyres, Dr Pepper machines, discarded air-conditioners, vending machines, empty and dirty Coca-Cola bottles, torn posters, power poles and power wires, street barricades, one-way signs, detour signs, No Parking signs, parking meters and palm trees crowding the same curb."

Eggleston has a unique ability to find beauty, and striking displays of color, in ordinary scenes. A dog trotting toward the camera; a Moose lodge; a woman standing by a rural road; a row of country mailboxes; a convenience store; the lobby of a Krystal fast-food restaurant -- all of these ordinary scenes take on new significance in the rich colors of Eggleston's photographs. Eudora Welty suggests that Eggleston sees the complexity and beauty of the mundane world: "The extraordinary, compelling, honest, beautiful and unsparing photographs all have to do with the quality of our lives in the ongoing world: they succeed in showing us the grain of the present, like the cross-section of a tree.... They focus on the mundane world. But no subject is fuller of implications than the mundane world!" Mark Holborn, in his introduction to Ancient and Modern writes about the dark undercurrent of these mundane scenes as viewed through Eggleston's lens: "[Eggleston's] subjects are, on the surface, the ordinary inhabitants and environs of suburban Memphis and Mississippi--friends, family, barbecues, back yards, a tricycle and the clutter of the mundane. The normality of these subjects is deceptive, for behind the images there is a sense of lurking danger."

It may help to compare Eggleston's work to the work of another illustrious Mississippian, William Faulkner, who also drew subject matter from the Mississippi Delta region that is the subject matter of much of Eggleston's art. Both Eggleston and Faulkner drew upon insights of the European and American avant-gardes to help them explore their Southern environs in new and surprising ways. As the writer Willie Morris wrote, Eggleston's "depiction of the rural Southern countryside speaks eloquently of the fictional world of Faulkner and, not coincidentally, the shared experience of almost every Southerner. Often lurid, always lyrical, his stark realism resonates with the language and tone of Faulkner's greatest mythic cosmos of Yoknapatawpha County .... The work of William Eggleston would have pleased Bill Faulkner ... immensely." Eggleston seemed to acknowledge the affinity between himself and Faulkner with the publication of his book, Faulkner's Mississippi, in 1990.

According to Philip Gefter from Art+Auction, “It is worth noting that Stephen Shore and William Eggleston, pioneers of color photography in the early 1970s, borrowed, consciously or not, from the photorealists. Their photographic interpretation of the American vernacular—gas stations, diners, parking lots—is foretold in photorealist paintings that preceded their pictures.”

Saturday, May 2, 2009

Everyone is invited......

thanks

Tuesday, April 28, 2009

Wednesday, April 22, 2009

Tuesday, April 21, 2009

Baby Photography

Monday, April 13, 2009

Monday, March 2, 2009

Chuck Close

Most of his early works are very large portraits based on photographs (Photorealism or Hyperrealism technique). In 1962, he received his B.A. from the University of Washington in Seattle. He then attended graduate school at Yale University, where he received his MFA in 1964. After Yale, he lived in Europe for a while on a Fulbright grant. When he returned to the US, he worked as an art teacher at the University of Massachusetts.

In 1969 his work was included in the Whitney Biennial. His first one man show was in 1970. Close's work was first exhibited at the New York Museum of Modern Art in early 1973. One demonstration of the way photography became assimilated into the art world is the success of photorealist painting in the late 1960s and early 1970s. It is also called super-realism or hyper-realism and painters like Richard Estes, Denis Peterson, Audrey Flack, and Chuck Close often worked from photographic stills to create paintings that appeared to be photographs. The everyday nature of the subject matter of the paintings likewise worked to secure the painting as a realist object.[2]

One photo of Philip Glass was included in his black and white series in 1969, redone with fabulous water colors in 1977, again redone with stamp pad and fingerprints in 1978, and also done as gray handmade paper in 1982.

"The Event"

On December 7, 1988, Close felt a strange pain in his chest. That day he was in New York about to give an art award. He begged to present first, went on stage, quickly read his speech and then ran to the hospital. Within a few hours, Close was paralyzed from the neck down. At first the doctors were confused but eventually they diagnosed a rare spinal artery collapse. Close called that day, "The Event". For months Close was in rehab strengthening his muscles; he soon had slight movement in his arms and could walk, yet only for a few steps. He has relied on a wheelchair since.

However, Close continued to paint with a brush strapped onto his wrist, creating large portraits in low-resolution grid squares created by an assistant. Viewed from afar, these squares appear as a single, unified image which attempt photo-reality, albeit in pixelated form. Eventually Close managed to recover some movement in his arm and legs, and now paints with a brush strapped to his hand. Although the paralysis restricted his ability to paint as meticulously as before, Close had, in a sense, placed artificial restrictions upon his hyper-realist approach well before the injury. That is, he adopted materials and techniques that did not lend themselves well to achieving a photorealistic effect. Small bits of irregular paper or inked fingerprints were used as mediums to achieve, nonetheless, astoundingly realistic and interesting results. Close proved able to create his desired effects even with the most difficult of materials to control.

Although his later paintings differ in method from his earlier canvases, the preliminary process remains the same. To create his grid work copies of photos, Close puts a grid on the photo and on the canvas and copies cell by cell. Typically, each square within the grid is filled with roughly executed regions of color (usually consisting of painted rings on a contrasting background) which give the cell a perceived 'average' hue which makes sense from a distance. His first tools for this included an airbrush, rags, razor blade, and an eraser mounted on a power drill. His first picture with this method was Big Self Portrait, a black and white enlargement of his face to a 107.5 in by 83.5 in (2.73 m by 2.12 m) canvas, made in over four months in 1968. He made seven more black and white portraits during this period. He has been quoted as saying that he used such diluted paint in the airbrush that all eight of the paintings were made with a single tube of mars black acrylic.

Later work has branched into non-rectangular grids, topographic map style regions of similar colors, CMYK color grid work, and using larger grids to make the cell by cell nature of his work obvious even in small reproductions. The Big Self Portrait is so finely done that even a full page reproduction in an art book is still indistinguishable from a regular photograph.

Close currently lives and paints in Bridgehampton, New York.

Tuesday, February 24, 2009

Kenyan Women Photo Project — visible from outer space

The hip, young French photographer, JR, likes to make his photographs larger than life and visible from afar. His most recent project in the slums of Kenya are designed to be visible from Google Earth satellites as well as from the elevated train tracks that pass by the village twice a day. The intention is to draw attention to the persistent strength of women in these struggling, poverty-stricken areas.

2000 square meters of rusty corrugated metal rooftops are now covered with photos of the eyes and faces of the women of Kibera, which is one of the largest slums of Africa. Most of the women have their own photos on their own rooftop, and the material used is water resistant so that the photo itself will protect the fragile houses in the heavy rain season.

The train that passes on the line through Kibera at least twice a day is covered with eyes from the women that live below it. With the eyes on the train, the bottom half of the their faces are pasted on corrugated sheets on the slope that leads down from the tracks to the rooftops. The idea being that for the split second the train passes, their eyes will match their smiles and their faces will be complete.

JR is what I would call a 21st century concerned photographer. He wants to call attention to important social problems, and he uses unusual materials and extravagant means to get his message out into the world. He has completed other audacious projects with people in Brazil, India, Cambodia, and other parts of Africa. And he's pasted smiling portraits of Palestinians and Israelis on both sides of the wall that divides them — showing how similar and human those on the other side look in reality.

For more information, check out JR's website. http://28millimetres.com/women/?ke

by jimcasper

The Transparent City

Heavy Light

Looking at the U.S. 1957-1986

Looking at the U.S. 1957-1986January 24 to May 24, 2009

Sunday, February 22, 2009

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

The Body as Billboard: Your Ad Here

Published: February 17, 2009

Ms. Gardner was among 30 of what the airline calls “cranial billboards.” For shaving their noggins and displaying the ad copy for two weeks in November, they received either a round-trip ticket to New Zealand (worth about $1,200) or $777 in cash (an allusion to the Boeing 777, a model in the airline’s fleet).

Jodi Williams, director of marketing for Air New Zealand, said half the participants selected the flight, because many were either New Zealand expatriates or, like Ms. Gardner, had visited and wanted to return. The participants were, in marketing parlance, ideal brand ambassadors: when co-workers or strangers behind them in the grocery store line asked about New Zealand, they could speak enthusiastically right off the top of their heads — so to speak.

Peter Shankman, author of “Can We Do That?! Outrageous PR Stunts That Work — and Why Your Company Needs Them,” applauds the airline for the “Tom Sawyer handing out paintbrushes” approach.

Wednesday, February 11, 2009

6 Painters and Photographers....